Rethinking sabbath

A conversation with Susi Krueger, director of Wycliffe Germany.

Wycliffe Germany’s theme for 2023 is sabbath. How did this decision come about?

A major part is that we have a lot of people who are tired—they have lost motivation or are dealing with burnout. The COVID season has not helped. Even in German society, people are talking about post-COVID effects in terms of people just being tired and burned out. And I’ve been thinking, how do we address this and how do we come back to a healthy rhythm and a healthy lifestyle that helps us work well and also rest well?

Susanne Krueger

That’s why I thought sabbath is a good topic for us—one, because it’s the godly rhythm that God has put into our lives and into creation. So, that’s what we should strive for. But also because Sabbath is not only about resting. It is also about working well. Six days you should work and one day you should rest. Sabbath is not against work. It is about a healthy rhythm of work and rest.

One of the other things I thought a lot about and want to challenge us in—because Sabbath has also to do with listening to God—is what kind of spiritual convictions do we live that might not actually come from God? Especially when time is pressing, we think, “Well, if I don’t do it, nobody will.” And I hear that so often. People are tired, they are sick, they have difficulties. They really need a break. And they say, “But if I don’t go back, these people will not get the Word of God.” Or “These people will not be able to know Christ.”

And I think, “Hey, that’s not actually our calling. God is doing that. Our responsibility is to do what God has prepared in advance for us to do. But the responsibility that people get to know Christ, that people are able to read the word of God … of course, he is sharing that responsibility with us, but it’s not our ultimate responsibility. It’s certainly not what God wants, I think, that we spiritualize our complete overworking. That we say, “Well, if God has called us to do that, he will give us the strength. And if that means working 20 hours a day, 7 days a week, God will enable us.” I don’t read that anywhere in the Bible.

We tend to look at ourselves as indispensable, don’t we?

Exactly. So those kinds of things came together and I thought, God has given us this rhythm. So let’s look at that and let’s see what God can teach us. Not only individually, but also as an organisation. What can God teach us about this healthy rhythm of work and rest that he has created for us to live in?

I don’t have any grand answers yet. We’re on the way. I want us to learn as an organisation about sabbath and the principles behind sabbath? As an organisation, how can we support a healthy rhythm of work and rest?

Are there specific steps you have taken as an organisation?

We have an internal newsletter once a month, and I’ve been writing about various things that I’ve read and learned about sabbath. When we have our monthly staff meeting, that’s a topic that we follow up on and talk about.

Sabbath for us also has to do with making room for God’s presence and God speaking. Prayer is very important to us. We meet every day here in the office for a half-hour devotion and prayer time. We have picture cards of all of our staff to pray for them and a prayer coordinator collects and prints out current prayer requests for that time. We are very good intercessors.

But every Monday now, we’re having a different type of half-hour where we just focus on listening to God. Maybe we sing a few more songs. Or we just divide out the picture cards—and without sharing requests, we just listen to God [to hear] what he gives us for the person in front of us. Or we do a Lectio Divina or something like that. Something different that helps train us to listen more and not just work down prayer requests. Because prayer can sometimes come to feel like work as well.

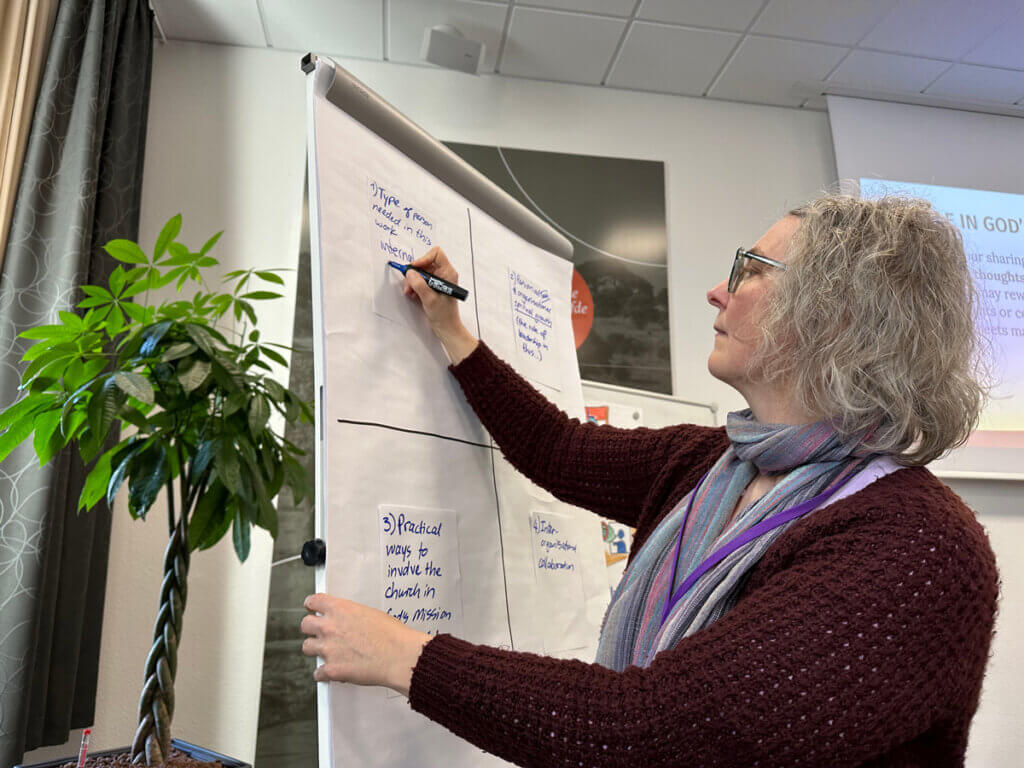

Susi Krueger at the first global "People" conversation which took place at Wycliffe Germany in January 2023. Others are happening throughout the world this year. Photo: Elisabeth Berg

How does the idea of sabbath work in German culture?

We still have Sunday as a kind of a non-work day. By law, most shops are closed. Supermarkets, drugstores, they are all closed on a Sunday. These days it unfortunately has less to do with churches and more to do with the unions. They are really strong about keeping that Sunday.

But there is still something immensely soothing and good about a communal day off. In German culture on a Sunday, in the early afternoon when the weather is good, you will see families and people just walking. You have a family lunch, and then you go walking. It doesn’t matter whether you are Christian or not. It’s just a cultural thing. I sometimes think that is actually a very precious cultural thing that we can build on. Because it is so much easier to rest when everybody else is resting as well.

On the other hand, this is of course very non-cultural because the borders between work and free time completely dissolve. It goes in waves. Younger people today are much more about having free space and work-life balance. My generation and the older ones, we are the ones who feel like we’re always working. We always need to be available and the work of God is never done—that kind of stuff. And it’s very difficult to just do nothing. You feel guilty when you do nothing. We have to relearn what it actually means to rest and to stop working.

You mentioned COVID and how that has made people so tired. What about it might have pushed us in a bad direction with sabbath?

In general, I think COVID has just added to the feeling of people being tired and exhausted and demotivated. And I think the reasons are manifold and quite different for different people. Some of it has to do with loss. A lot of us have lost people. I lost both my parents during COVID and my dad actually died of COVID. They were 74 and 76.

So for some it was a very personal loss. And then for us singles, our normal way of spending time and recharging—going walking with people, going out for dinner with friends—that was all taken away.

Pete Scazzero’s book, The Emotionally Healthy Leader, has a really good chapter on sabbath. He says stop, rest, enjoy and contemplate God. The “enjoy” part was taken away from a lot of us singles. Whereas for a lot of families, it was just enormous added stress because of weeks and months and even years of homeschooling and having kids at home 24/7—which was really, really hard on some parents in trying to juggle. You had families where all of a sudden, the kids were doing school from home. The dad was at home, trying to do work from home. The mom was at home, trying to do work from home, and everything was completely different. And that was hugely stressful on families.

And then especially for older people, there was no way of connecting any longer and then the fear of getting sick came on top of that.

So I think it was just a lot of changes connected with COVID and also anger—anger at people not understanding your point of view because of course we all had different views. Anger about the government all of a sudden putting down laws where you felt, “You can’t tell me not to celebrate my birthday with my family just because it’s more than three people!” Lots and lots of stuff.

As you mentioned, sabbath is more than simply not going to work for a day. You’re taking a more holistic point of view.

It was quite interesting last year when I talked to my counsellor about this whole thing and she said, “Susi, great stuff that you’re thinking about that for Wycliffe work. But why don’t you think through it for yourself first?” I thought, “True. I think you’ve got a point there.

I am on a journey myself. I realised little things like being very conscious that sabbath is far from not going to work and lounging on the sofa and watching reruns of Game of Thrones or something. That’s not sabbath.

So what is sabbath?

I think it is about an inner kind of perspective. For example, one of the things I read and started telling people is, there are two instances in the Pentateuch where the Ten Commandments are listed. In the first list, the reason given for the sabbath is because God rested after six days. So the creation order is why the Israelites were supposed to hold the sabbath.

When you look at the second list, the completely different reason given is, you should hold the sabbath because God has taken you out of slavery and brought you into freedom. One Jewish writer says, in slavery the Israelites were under a life-threatening and a life-despising regime.There was no free time or rest beyond the bare minimum of sleep needed. But God is a life-giving and life-affirming, God. When we hold sabbath, we say that’s the lordship we are under. We are not under a slave-driving, life-threatening majesty, but we are under the one life-affirming God who gives us time to rest and enjoy.

We also proclaim that God is very well able to run this world without us for a day. He can handle it. I think I’m realising as I go on this journey how big a difference that thinking makes. It’s not just stopping. It is also finding good ways of resting. It is finding good ways to enjoy. One writer says, God didn’t really need to rest. God doesn’t get tired. But he looked at creation and it was very good. He enjoyed creation on that seventh day. We’re supposed to enjoy that day, too.

And then there’s a passage in Isaiah (58:13-14) where it says, if you keep the sabbath as your delight … then you will find your joy in the Lord. Sabbath should be a delight. And it’s a day when we contemplate God, when we go to church, when we have communion with other Christians. We think about God. We give God room to speak to us. So all these things come together.

Wycliffe Germany makes prominent mention of Vision 2025 on your website. In a way, as that year draws near, it might feel counterintuitive that you are also emphasising sabbath.

We’ve always had Vision 2025 very upfront and we still do. I think for us and for myself, Vision 2025 has already probably done what it was purposed to do. It doesn’t matter too much whether we actually managed to start every language or not. That’s not the vital part. I think our way of working has fundamentally changed because of Vision 2025.

Yet, the urgency is still there. But especially when it’s urgent and especially when we feel we have too much to do, the more important it is to have a good discipline of sabbath.

Pete Scazzero calls it a necessary spiritual discipline to hold Sabbath. It’s not a law. We are not under the law any longer, but it is a very important and necessary spiritual discipline that helps us to grow and helps us to come closer to Christ.

What would you say to other Alliance leaders about this topic of sabbath?

For us as an Alliance it is an interesting question. How can we support each other and help each other in respecting these boundaries that we have? We talked this morning as a staff about the topic, what does it mean to stop work?

We talked about our own responsibility to create our own boundaries. We have so many even technical possibilities to do that these days. But it’s also to respect other people’s boundaries. I caught myself on Sunday. I was away over the weekend, came back and emptied my letterbox. And I had a letter there that had to do with some insurance stuff. The person where I have my insurance is a good friend of mine as well, from church. And so I just took a picture of that one letter and sent it to him because he needed to have that. And he answered, “I’m going to deal with that tomorrow.”

I felt convicted and wrote back: “I’m so sorry. I shouldn’t have sent you that on a Sunday evening.” It’s those kinds of boundaries for others—as an alliance, as a group, as well as an organisation. How can we help each other, in listening to God and in respecting boundaries, and maybe even enjoying Sabbath together?

I don’t know what that could look like. That’s one of the things that we want to try out and think about. What does that mean for us as a Christian community? Where we work here in the office, we are a very close team, in some sense a close community. Then the Alliance is the other extreme, a very loose community when you look at it as a whole. But how can we live this sabbath rhythm in a way that it encourages each other, and that we might even find some of that delight together?

Interview: Jim Killam, Wycliffe Global Alliance

Alliance organisations may download and use the images from this article.

The latest

View all articles

03/2024 Pacific: Papua New Guinea

Informing, teaching, inspiring: PNG workshop teaches video storytelling for language communities

PNG workshop teaches video storytelling for language communities

Read more

02/2024 Global

Looking ahead at 2024

As the year unfolds, we marvel at the work of God in our rapidly changing world. And, we look forward to a number of gatherings and conversations intended to draw us together.

Read more

01/2024 Americas

Telling the Bible's Story

It may come as a surprise that a museum is among the Wycliffe Global Alliance organisations.

Read more