Desmond Tutu: Giant of Grace

A pastor and member of South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission remembers his friend, Archbishop Desmond Tutu. This interview took place in December 2020 for a story about Bible translation and reconciliation.

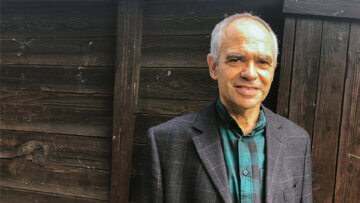

Archbishop Desmond Tutu in 2010. Photo: Nathan King / Alamy

Retired Anglican Archbishop Desmond Tutu died Sunday (26 December) at age 90. Tutu not only helped end apartheid in South Africa, but in the mid-1990s he chaired the country’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission. Those hearings brought black and colored victims and their families face to face with white authorities who had committed atrocities.

When apartheid ended, the world expected South Africa to descend into civil war, perhaps even genocide as blacks took revenge on their white oppressors.

Tutu saw a different path.

Prof. Piet Meiring preaches to the 2016 SIL ICON and Wycliffe Global Gathering participants in Chiang Mai, Thailand.

“He thought that through the love of Christ and by the process of grace, reconciliation would come about,” said Piet Meiring, a South African Reformed theologian and pastor whom Tutu appointed to the TRC.

As the commission prepared for its first hearings, Meiring remembers, friction arose over the leadership style of the man affectionately known as “Arch.”

“People said to him, ‘Look, Arch. You are not the Archbishop of Cape Town anymore. You are now chairperson of a commission that was launched by the state, by the parliament. You’re not working with the Bible, you’re working with an act of parliament under your arm. Please, no biblical references, no prayers and no hymn singing.’”

Tutu thought for a moment. “OK,” he said. “If that’s the way you want to do it, let’s try it.”

Meiring smiled as he continued the story. “But of course he still had his red cassock on, with his cross on his tummy.”

The hall where the hearings would be held was packed — family members, government officials, accused perpetrators. Tutu entered and, as he always did, greeted everyone within a hand’s reach. Then he approached the podium solemnly.

“I was directed by the Johannesburg office that this will be a secular hearing. We won’t pray. We won’t sing hymns. But let us allow ourselves to do what we do when we open Parliament nowadays. Let’s have a moment of silence for those who want to meditate before we start.”

After the quiet moment, Tutu started the meeting. The first victim entered and she was sworn in.

“Tutu was never at a loss for words, but he couldn’t start,” Meiring remembers. “He couldn’t speak. He was shifting in his chair back and forth. He cleared his throat for an uncomfortable three to four minutes.

“And then suddenly he looked up at the audience and said, ‘No, no, no! This is not the way to go back. We will pray. Close your eyes.”

“And then he prayed a wonderful prayer to Jesus Christ, who is the font of truth, to lead us, and to the spirit of God to guide us along the way. And when he said amen, he smiled and said, “Now we will sing.” And he found a well-known hymn, and the whole audience arose and they sang with him.

“And then Tutu smiled and said, “I think we are ready to start.”

Biblical roots

“Without the biblical message of peace and reconciliation, of the gift of grace, reconciliation becomes very, very difficult,” Meiring said. “South Africa had just discovered itself not only as a new, democratic country, but also as a secular country where the roles of the churches and the faith communities were played down a bit.

Tutu was so internationally revered that even those who opposed him realized that South Africa was still a religious country, too. “There’s no way by which you can talk about reconciliation and justice and forgiveness without reaching out to the deepest sources of your faith,” Meiring said.

“He was so fond of 2 Corinthians 5, where Paul pleads for reconciliation because God has reconciled us with Christ. And that was the example. But then Tutu very interestingly said, ‘But we Christians, we do not own everything.’ He called upon the Muslims and the Hindus and the Jewish community also to go back to the fountains of their faith to see what they could bring toward the process of reconciliation. Which they did.”

‘What about justice?’

Grace can be a hard message for people of any faith, Meiring said.

“Some people … said to Tutu and the others, ‘You are making things far too easy. You just say ‘Let us forgive and forget.’ It’s not that easy. What about justice? What about retribution? What about paying back what has been taken from you?’”

At the very last TRC hearing, faith communities were invited to talk about their own histories, confessing what needed to be confessed and then committing themselves to peace and reconciliation.

“That was quite an experience,” Meiring said, “having the white Afrikaans (Dutch Reformed) churches trying to explain why they fell for the apartheid theology and eventually came to their senses and asked for forgiveness for the pain they had inflicted upon others. And on the other side, the magnanimity and the grace of the other churches — often the churches of victims — who reached out and said, “If you confess, we accept your confession and we embrace you.”

“Tutu often said, ‘Remember, we ask for forgiveness, not for amnesia. We don’t want to whitewash what has happened in the past.’ I think we came to realize that grace and forgiveness do not come cheap. We saw wonderful examples of reconciliation in our process. It often went with times of anguish and real tears.”

Story: Jim Killam, Wycliffe Global Alliance

Related story from 2021: Stephen Coertze, the Wycliffe Global Alliance Executive Director, remembers his own powerful experience with grace and reconciliation in South Africa.

The latest

View all articles

03/2024 Pacific: Papua New Guinea

Informing, teaching, inspiring: PNG workshop teaches video storytelling for language communities

PNG workshop teaches video storytelling for language communities

Read more

02/2024 Global

Looking ahead at 2024

As the year unfolds, we marvel at the work of God in our rapidly changing world. And, we look forward to a number of gatherings and conversations intended to draw us together.

Read more

01/2024 Americas

Telling the Bible's Story

It may come as a surprise that a museum is among the Wycliffe Global Alliance organisations.

Read more